Lesser-Known Languages (LKL) - Taiwanese Hokkien / Tâi-Gí

Part 1: Arrival in Taiwan and evolution

Despite having never been to Taiwan, I’ve been extremely interested in that country since the beginning of my journey with Mandarin. In fact, the very first time I thought Mandarin didn’t sound awful was through a song in Mandarin by the Taiwanese singer Rainie Yang (楊丞琳).

That song was the trigger for me to get interested in Mandarin as a whole, although the first 8-9 years were completely focused on Mainland’s Simplified Chinese. I turned to Taiwanese Chinese (using traditional characters) little by little over these last 5 years.

As I watched Taiwanese dramas, I saw how much Korean and Japanese cultures were appreciated in Taiwan. This made me even more curious about Taiwan as I love both of those.

I learned about the variety of languages existing in Taiwan through Glossika founder Michael Campbell.

I was shocked to discover there are as many as 16 languages and 42 accents of the indigenous languages on such a small island.

Since then, I’ve looked into many of them. Notably, Atayal and its remaining speakers grabbed my attention for a while.

But Taiwanese Hokkien picked my curiosity even further.

I wondered how it could be spoken by most of its population without being an official national language1. I needed to know more about this.

My journey into learning this language’s origins, basics, and its growth was inspiring. Despite having only spent about a month and a half on it, its musicality and long history have hooked me.

Hokkien before Taiwan

Taiwanese, known as Tâi-Gí in the language, was originally called Taiwanese Hokkien. It’s the Taiwanese version of Hokkien.

So what is Hokkien? Where does it come from and why did the Taiwanese version get its own name?

Hokkien is a Southern Min language that originated from the Fujian province in the southeastern part of Mainland China. The name comes from the Hokkien pronunciation of the Fujian province’s name.

China’s long history has allowed many varieties of Chinese to develop. Mandarin became the national language by the early 20th century because it was the variant spoken by most people but it originally wasn’t more than one of the Chinese variants.

While Mandarin, Hakka, and most other variants of Chinese come from Middle Chinese, Southern Min2, spoken in the southeast of China, comes from a different branch of Chinese: Old Chinese.

Hokkien, being one of the languages coming from Southern Min, therefore also comes from Old Chinese. This being said, it evolved alongside Middle Chinese which impacted it as well.

Fujian province is a mountainous area so it was difficult to travel around it. This caused the Southern Min languages like Hokkien to diverge from area to area. The most common dialects of Hokkien today are Quanzhou, Zhangzhou, and Amoy.

During the Uprising of the Five Barbarians (304 CE to 316 CE), many northern Chinese migrated to the Fujian province, bringing their languages. Many colloquial readings of Chinese characters came from them.

Indeed, Chinese characters can often have two readings: colloquial and literary.

For example, 學 in Hokkien can be read as “hak” in its literary pronunciation—as in 學生, hakseng —but as “oh” in its colloquial one—as in 學堂, oh tng. Mandarin, however, often sticks to one pronunciation (in this case, “xue”: xuesheng and xuetang).

Hokkien has 40% of its characters with two pronunciations!

This is due to it taking influence from Old and Middle Chinese. Indeed, its colloquial readings come from Old Chinese and the literary ones from Middle Chinese taken during the Tang and Song Dynasties.

The end of the Ming Dynasty was plagued by wars and chaos. Many people from the Fujian area wanted to flee the conflict. And, as mentioned earlier, Fujian is surrounded by mountains. The other way out? The Taiwan Strait.

This is when the Hokkien language landed on the island around the 1600s as emigrants left the Fujian province to go to Formosa (the name of Taiwan at the time). Some spoke Hokkien, some Mandarin, some other Hakka (mostly from the two prefectures of Zhangzhou and Quanzhou).

By the 18h century, the Taiwanese population coming from Fujian was over one million.

It was also at that time that people from Fujian began spreading throughout Southeast Asia.

Hokkien outside of Taiwan

Hokkien is still spoken to this day in the Fujian province. There are approximately 23 million speakers of the language there. The language demonstrates a few differences between the three main dialects: Zhangzhou. Quanzhou, and Amoy (Xiamen).

Outside of Mainland Chinese and Taiwan, the diaspora of Hokkien speakers has spread. It is now the lingua franca of most Chinese diasporas in the countries mentioned below, although Mandarin is also commonly used.

The first of all is the Southern Malaysian Hokkien. Hoklo people began migrating to Malacca (Malaysia) in the 15th century. They were known for their trade in the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaya (current Malaysia), and Siam (current Thailand).

This migration included people from all regions but it appears the variant that stuck in the South of Malaysia was the one from Quanzhou. It has also been heavily impacted by Singaporean Hokkien due to its proximity.

On the contrary, the Penang Hokkien, spoken in the north of Malaysia, and the Philippine Hokkien are largely based on the Zhangzhou dialect. The Medan Hokkien language, spoken in Indonesia seems to be based on it too, although they mostly rely on romanized letters as Chinese Characters were banned in 19673.

Singaporean Hokkien, despite being rather recent4, seems to be the most prevalent form of Hokkien outside of Mainland China and Taiwan as most videos and documents showing up when researching information about “Hokkien” tends to come from there. It might also just be that speakers of this variant are more vocal and supportive of their language though.

All these variants of Hokkien have evolved in their own ways while being impacted by the other languages spoken in each country. This means certain loanwords can make conversing with someone in another country difficult.

Taiwanese Hokkien’s special sauce

It would be overly simplistic to consider Taiwanese Hokkien as a simple version of Hokkien. Its long and difficult history in Taiwan has given it a flavor not found in any other area where it is spoken.

And nothing could prove it more than its writing system.

Tâi-Gí letters

My original expectation about Tâi-Gí was that it used Chinese characters (Hanzi) like any other language of Chinese origin. While somehow true, the situation is a lot more complicated.

Tâi-Gí currently has many ways to be written. Before we get to the currently most used ones, let’s go through the honorable mentions:

Taiwanese Kana: A writing system based on the Japanese katakana, used during the Japanese occupation, 1896 to 1945, (as a way to teach Japanese to Taiwanese people). It uses small kanas for final syllables (similar to the katakana used for Ainu)

Taiwanese Hangul: A writing system created in 1986 and based on the Korean Hangul alphabet. It never really caught on but is said to be extremely simple to use for those who can read Hangul.

Bopomofo: Used in combination with Chinese characters, this typical Taiwanese phonetic system was thought to make reading Hokkien faster.

Taiwanese Language Phonetic Alphabet (TLPA): This romanization scheme created in the late 1990s and pushed by the government from 1998 to 2006 required no special character or tone mark. Instead, it doubled letters when needed and used numbers after each syllable to indicate the corresponding tone.

Hàn-lô (漢羅): This is a popular hybrid approach that was developed in the 1960s. It uses characters for direct Mandarin cognates and Latin script of the remaining 15% of Taiwanese words that don’t have easily recognizable characters. For example, Thian--leh! (in POJ, meaning “Listen!”) became “聽--leh!” in Hàn-lô.

Homogenizing the script has been a difficult endeavor for the Taiwanese government ever since the island’s independence. As a result, today’s writing system is still a tricky subject. There are three main ways used to write Tâi-Gí:

Chinese characters: While this system can seem the most convenient for a language of Chinese origin, Tâi-Gí’s tones and use of different readings for the same character have made it impractical. Still, this is currently the most used writing system along with the next one.

Pe̍h–ōe–jī (POJ): This Latin-based script was created by Spanish missionaries in the Southern Min region. It caught on in Taiwan and became a convenient way to write in Tâi-Gí without the inconvenience of having different pronunciations for one way of writing.

Tâi-lô5 (TL): This Latin-based script was created in 2006 by the Taiwanese Government. It is quite similar to POJ and TLPA but also closer to the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). As this is pushed by the government, this writing system is becoming more common but some argue for sticking to POJ.

Growing under pressure

During the Japanese occupation, using Taiwanese was forbidden. The language survived through the spoken word at home but also incorporated Japanese words in its vocabulary, such as iá-kiû (野球) that came from the Japanese 野球 (yakyuu, baseball).

In fact, certain expressions like アタマコンクリ (atama konkuri, meaning “obstinate; inflexible; stubborn” and coming from the Japanese 頭が固い “atama ga katai”) came from the use of Japanese on the island. As a result, many Taiwanese expect Japanese people to understand “atama konkuri” despite the expression not being from Japan itself.6

In a fit of irony, it was the Japanese occupation that triggered a nationalism sense in the population. Before the occupation, migrants to Taiwan referred to themselves as people from their region of origin. The colonisation changed that, which contributed to the language growing as well.

The Japanese rule came to an end in 1945 but it was immediately taken over by the Chinese Kuomintang (KMT) governement. This authoritarian governement imposed the Chinese identity over the other indigenous ones until 1987. During what was the longest martial law imposed in the world (1949-1987), Tâi-Gí was prohibited in public places.

During that time, the Taiwanese identity got closer to the Chinese identity and further away from the original Taiwanese one (and the previously imposed Japanese identity).

It was only when Taiwan began a democratisation process, in 1987, that Tâi-Gí started being spoken outside homes again.

Taiwanese Hokkien in numbers

As already mentioned, Taiwanese Hokkien has more than one name. In fact, it has many more than the ones I already gave. It can be called Tâi-Gí, Tâioânese, Tâi, Taiwanese Minnan, Hoklo, Holo, or simply Taiwanese.

I suppose it is because it’s such an important part of Taiwan that this language and not another like Hakka became known as Taiwanese.

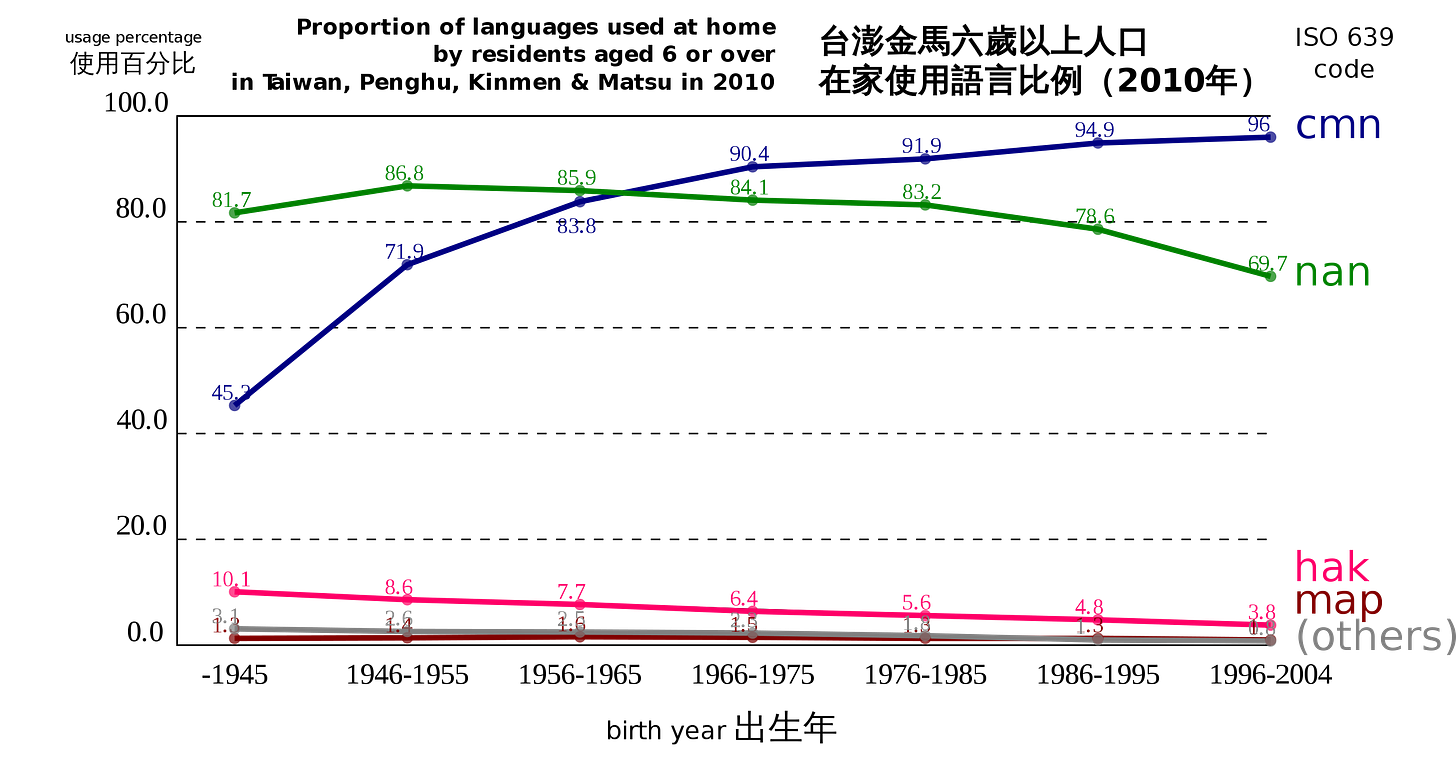

Taiwanese is spoken by 70% to 80% of the population and is the lingua franca for daily tasks. A census from 2010 showed a difference of only 1.6% in the number of speakers between Mandarin and Taiwanese (83.5% vs 81.9% respectively).

The same census also showed a decreasing number of young people speaking Taiwanese compared to Mandarin.

This, however, is data from the 2010s, back when Taiwanese wasn’t an official language with support from the government.

Indeed, Taiwan made Taiwanese—along with 15 other indigenous tribes’ languages—an official language only in 20177. Since then, there have been more activities toward developing the language.

One strange fact about the number of Taiwanese speakers is that every source I found either said there were 70+% of the population speaking it (16+ million people) or 13.5 million speakers (~57%). I suppose this might be because one only counts native speakers while the other counts non-native speakers, but I have not found proof of this guess.

Taiwanese is still rarely spoken in formal settings but more and more companies are transitioning into offering services in both languages. This is especially true for Government-related affairs, as the 2018 National Languages Development Act granted the right to use one’s native language when accessing public services.

An intrinsic construction

And so we come to the discovering of the Taiwanese Hokkien language itself.

There was so much to say about this beautiful language that I had to divide this piece into two parts.

Click below to read the next one!

And let me know if you think I missed some important parts about Taiwanese Hokkien’s history (or got some wrong)!

Whoops, as you’ll read soon, it seems my belief was wrong!

Other Min languages also come from Old Chinese.

This ban was lifted in 1992 but the impact is still felt to this day.

The migration of Hoklo people to Singapore started only from 1820 onwards as Singapore was starting to become a trading hub.

Its full name is a bit more complicated: Tâi-uân Lô-má-jī Phing-im Hong-àn

コンクリ comes from コンクリート, which means “concrete”

This also included 42 dialects within those 16 languages.