Lesser-Known Languages (LKL) — Tayo Creole

A creole language growing on an island with 30 languages.

I’ve been looking into Creole languages for over a year, mostly digging into some largely spoken yet lesser-known ones like Papiamento and Sranan Tongo. All the Creole languages I’ve found have amazed me with what seemed like curious evolutions.

You see, I grew up thinking “Creole” was one single language. I thought it was some kind of broken French1 people from places that were previously French colonies had come to speak to survive French occupation.

I couldn’t have been more wrong.

There are many Creole languages and even those with the same “base language” have evolved in their own specific manner. This is why we can find videos like this one where a speaker of one French-based Creole language cannot understand the other French-based Creole sentences or only a part of them.

As we’re turning again to Creole languages this month, I wanted to showcase one that strayed from the rest even further.

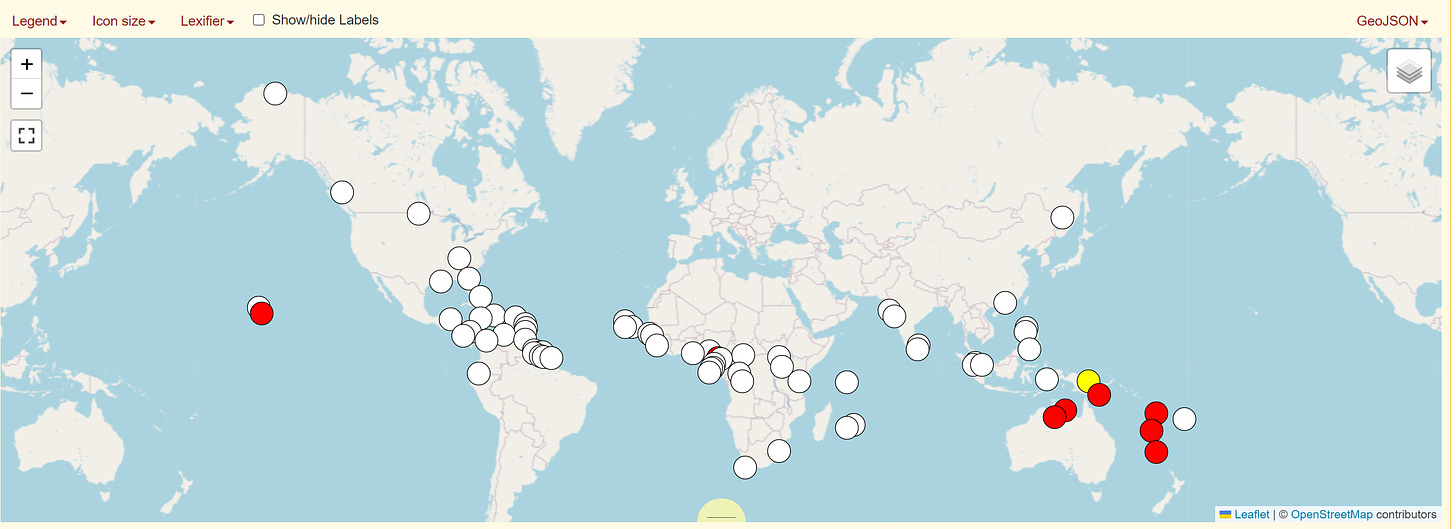

That’s when I found Tayo, the only creole language in the Pacific Ocean.

With the closest other French-based Creole over 11,000 kilometers (6,800 miles) away, its evolution is its own. In fact, it’s also a relatively young Creole language growing on an island where the population’s pushing to bring back its indigenous identity known as Kanak.

Depending on where you look today, resources indicated a population of 900 to 1,500 speakers. Considering its origins, it’s already proof enough that it’s grown a lot but it’s also beginning to grow outside its borders.

What could make the only Creole language in New Caledonia, an island with 30 other languages, grow?

That’s what I wanted to know.

Tayo’s history

The French established their first permanent settlement in New Caledonia2 at Port-de-France (now Nouméa) in 1854 but it wasn’t until the opening of the nearby Saint Louis’s Girls’ Mission school that Tayo’s roots took form.

In this school, Kanak girls were taught in standard French, and using their native Kanak languages (the island has about 30) was prohibited. Still, using a new language was difficult and some Kanak features took slipped into their daily language.

Once they got married to the men working in the field who had less access to French, their common language—a modified simplified French—became their children’s first language.

This was the beginning of Tayo.

As New Caledonia became a penitentiary, people from other cultures arrived and Saint Louis became a sort of manufactured “creole society.” The ban on Kanak culture and its languages only strengthened the need for a language like Tayo.

Since the end of the last century, locals have pushed for the development of Kanak cultures and languages. The Academie des Langues Kanak (ALK, Academy for Kanak languages) was created after the Noumea Accords in 1998. It now has a webpage (in French) with basic information about the 28 Kanak languages that still exist… and yet Tayo doesn’t get the same treatment.

Despite some of its influence coming from Kanak languages, it is considered a Creole language and is mostly left alone.

And yet, the language seems to be growing.

Because most people have grown up using French and Kanak languages3 are widely different from it, going back to learn them is hard. Tayo has become a good solution toward which people can turn.

Only time will tell how Tayo will evolve but it is changing rapidly with each generation. As one 28-year-old speaker, Théodore Wamytan said:

« Ça évolue vite, Je ne parle pas le même tayo que ma mère, ni même que les gens qui ont 20 ans de plus que moi ». (It’s evolving quickly. I don’t speak the same Tayo as my mother, nor the people who are 20 years older than me.)

The researcher Sabine Ehrhart also noticed some structural changes and developments between her two trips in 2003 and 2006, another clear proof of the evolution of this young language.

Tayo language

Alright, talking about the language, let’s turn to what’s been researched and used so far. Of course, considering Tayo’s evolution, it is possible all the following information could become obsolete one day.

Overall

As far as I’ve seen, it doesn’t look like there’s an agreed way to write Tayo. I’ve seen the word “me” written both as mwa and moa (both from the French “moi” which has the same pronunciation). I’ve seen the mwa version as a common evolution in multiple French Creole languages but the Kanak Languages Academy’s music in Tayo writes it in the second version.

The few places where we can find written Tayo are research papers and Wikipedia and it seems they’ve all chosen to rely on the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) so we can see the y pronunciation written as j, as in larivjer (the river, from “la rivière”).

Tayo is unfortunately considered of lower status, so it is mostly spoken in families which is probably why its writing system isn’t so stable currently.

Tayo has followed a similar evolution to that of Seychellois Creole when it comes to articles. In the example above, the actual translation of larivjer can be simply “river.” In short, in some cases, the definite article has merged with the noun itself.

As a result, “the river” is larivjer but “a river” is a larivjer, with a meaning “one.”

Tayo mostly follows the word order found in French: Subject-Verb-Object. It doesn’t have genders. Both these are common features of Creole languages.

Particularities

Like many other Creole languages, many of the language’s evolutions have come from people speaking the language quickly.

This being said, it feels like Tayo has gone further than others. For example, while “for me” is said as pou mwin in Reunion Creole or pour mwan in Seychellois Creole, one of Tayo’s forms is pwa.

This is the contracted form of pur mwa that evolved into pu mwa then pmwa and finally pwa.

When it comes to possession, Tayo post-positions pu + [personal pronoun in its reflexive version]. Indeed, “my house” is said as kas pu mwa, literally "house for me” (“maison pour moi”). This is also interesting because most other Creole languages rely on the French word order. It would be “mon lakaz” in Seychellois Creole for example.

Another particularity of Tayo is its use of dual pronouns, something inexistent in French and most other Creole languages. In fact, it seems there’s only one Creole language (Pidgin Hawaiian4) outside of the region using dual pronouns.

Indeed, Tayo has nunde, vunde, and lende. They could be translated as “the two of us,” “the two of you,” and “the two of them.”

I haven’t been able to pinpoint the exact origin of dual pronouns in Tayo but it probably comes from the influence of some Kanak languages that have dual pronouns, such as the Drehu language.

Contrary to many other Creole languages that add plural markers only for emphasis, Tayo does express the plural, with tule, tle, or te preposed to the noun it refers to. “The rivers” would therefore be said te larivjer.

I can’t help but wonder if these forms aren’t from the French “tous les…,” an expression that means “all the…” 🤔

Finally, the term la (meaning “there” in French) often follows nouns and serves to put an emphasis on the noun. It can sometimes be translated as a demonstrative as in kas-la, “this house.”

Tenses, Negation, and Modality

Tayo does not conjugate its verbs based on the subject. Instead, it uses aspect markers right before the verb in its one and only form.

The present, near-future, present progressive, and even the past in some situations, are all express simple by using the verb in its original form:

Ta ekri → You write.

Ta ekri kwa? → What are you writing?

Ta fe kwa se swar? → What are you doing tonight?

The past uses ete (from the French imperfect form of the verb to be, “était”):

On ete arive. → We arrived.

Jer ma ete ekri. → I wrote yesterday.

This seems to be a form mostly used by the younger generations, probably influenced by their usage of French. Older people instead rely on using the particles fini or ndja instead, as in:

Ma fini reste Paris. → I lived in Paris (but now am living elsewhere).

The future uses the particle va (from a form of the verb “to go” in French)5:

Ma va reste Seoul. → I will live in Seoul.

Finally, the progressive uses atra nde from the French “(être) en train de”:

Lesot6 atra nde fe kwa? → What are they doing?

La atra nde malan. → She’s (currently) sick.

This second example of the progressive is a special usage found in Tayo only. It serves to signal the current relevance of the state. Like many other aspects in Tayo, I’m unsure of where this originated from though.

The negation works similarly to other Creole languages. The particle pa (from the French “pas”) is added in front of the verb and any other particle that goes with it, except the future particle:

Ma pa ule. → I don’t want./I don’t like to.

La va pa ale. → She won’t go./She won’t be going.

Tayo uses modality markers as prepositions to create more complicated sentences.

For example, the verb ule found in the previous example means “to want” (probably from the French “vous voulez,” “you (pl.) want”) and can be used as a modality marker as in:

Me person le ule ale. → But nobody wanted to go.

The marker fo (from the French “il faut”) indicates an obligation:

Fo ale vit. → [You] have to go fast.

Fo parle tayo. → You have to speak Tayo.

The marker mwaja (nde) from the French “moyen de” (“means to”) is used to indicate the an external ability to do something:

No, la pa mwaja vja. → No she cannot come.

For an intrinsic capacity, the marker kone from the French “connaît” (“knows”) is used instead:

Lesot kone parle tajo. → They can speak Tayo.

Questions can then be created simply by raising the intonation at the end of the sentence without changing the word order:

Pater pu twa va vja? = Pater pta va vja? → Will your father come? (Your father will come?)

For interrogations using question markers, the marker often comes at the end, but it can also be inserted in the middle of the sentence if required:

Sa (a)tra nde fe kwa? → What are they doing?

Lesot war ki? → Who did they see?

Frer pu ta se ki? = Se ki frer pu twa? = Se ki frer pta? → Who is your brother?

A few more sentences

Ma fini bwar dodo-la. → I drank the water.

(Se) twa le fe sa. → You’re the one who did it. [is you it do this]

La vya ka? → When is she coming?

Nu (va) asi! → Let’s sit down! [we (FUTURE) sit-down]

Si ma ale sa lui, ma truve sola. → If I go to St. Louis, I will meet them.

La ule (ke) lesot vja. → She wants them to come. [she want that they come]

Where to Learn

As a language with only a few speakers and only starting to grow within New Caledonia’s borders, Tayo lacks online resources to study from. The two main problems are the absence of a freely available dictionary and audio content.

Despite all my research, all I found was the music above and this short video of a person talking about Tayo. While it’s better than some other lesser-known languages (such as Rotokas which had only one video), it’s clearly not enough to get used to the rhythm of the language.

If you wish to learn more, about the language and its structure, the page about Tayo in the Atlas of Pidgin and Creole Languages Structures Online (APICS) will be your best bet. Wikipedia also has some information but it’s mostly a copy of this one.

Finally, if you speak French, this research paper and this article from 2022 are great reads to learn more about the language and its current status.

Final thoughts

Tayo is the kind of language that makes me hopeful about the future of the world.

It proves once again a language can grow from a small community and strive despite all the pressure from others.

It all started from a small settlement and the need for communication evolved through the generations and is now growing even outside of the area. It doesn’t rely on a need to communicate anymore. It’s expanding because people want it.

Seeing such a language makes me think often of the future of other natural languages. I often come to the conclusion the world will one day be filled mostly with Creole languages as we keep mixing.

Whenever I think about this, the constructed language Belter Creole comes back to mind. I wrote about it before so you can check it by clicking here.

See you next week for the seventh edition of TL;DR!

I’m glad I don’t think this anymore!

Fun fact: Caledonia is the Latin name for Scotland. When Captain James Cook found the island in 1774, he thought it looked like Scotland which is why he gave the island its name of New Caledonia.

Kanak languages were forbidden in public spaces until 1970.

So, technically, not a fully-fledged Creole language.

Using the verb “to go” to express the future is a common feature in French, as in the English “to be going to.”

Lesot probably comes from the French “les autres” which means “the others,” a funny way to say “they” if you ask me!