Lesser-Known Languages (LKL): Bugis

A language not using its own beautiful script

Choosing a new language to dive into each month is always an interesting journey for me.

I scrape the internet looking for the one language (in a geographical area) that’ll capture my interest. As we’re turning to Southeast Asia this month, I knew I’d struggle settling on one because I’d get to see some magnificent scripts.

And, gosh, was I right.

As you’ll see later this month too, there are some pure beauties in Southeast Asia. For this deep dive, I almost dove into the Wa Language in Myanmar but decided otherwise in the end because I’d first like to improve my Burmese.

And when a random link brought me to Bugis, I knew this exotic yet familiar script deserved my attention.

Why familiar? Because it really reminds me of conlang Toki Pona’s letters, even though I couldn’t find a single sentence linking the two scripts. Then again, the Lontara script used in Bugis is an abugida.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. More on that later.

First, where the hell is this curious language spoken?

History

The Buginese people, or simply Bugis, are an ethnic group found in the South Sulawesi province, in Indonesia.

Despite my having never heard of the term, it appears the Bugis still count for 7 million of the 273 million people in Indonesia. It might seem little in proportion but that’s still more than the entire population of Denmark or Bulgaria.

In the early days, around the 14th century, the Buginese established several kingdoms, including the powerful kingdom of Bone and Wajo. These kingdoms were known for their maritime prowess and trade networks, which extended as far as the Philippines and Australia.

Things started to change in the 16th century with the arrival of the Europeans—as history usually goes. The Portuguese were the first to arrive, seeking to control the lucrative spice trade. They were followed by the Dutch in the 17th century, who established the Dutch East India Company and began to exert their influence over the region.

The Buginese, being skilled warriors and diplomats, initially managed to maintain a degree of autonomy by playing the European powers against each other, forming alliances when beneficial and resisting when necessary.

Over time, the balance of power began to shift.

By the 18th century, the Dutch had gained the upper hand. They implemented a system known as the 'Kongsi contracts,' which effectively turned the Buginese rulers into vassals of the Dutch East India Company. This marked the beginning of a period of direct Dutch control over the Buginese kingdoms, which lasted until the early 20th century.

The Dutch rule over the Buginese kingdoms ended in the early 20th century when Indonesia declared its independence.

Cultural genders

One of the most shocking surprises in my research about Bugis was a cultural aspect.

The Buginese people recognize 5 genders.

And they have for centuries.

As a man born in Europe and who grew up in “Western cultures,” I have seen the evolution of transgenders and the LGBT-Q community in Europe and the US. And so, I was quite stunned to see another culture on the other side of the world not only embrace other genders without compromise but do it for centuries.

Again, the Bugis recognize 5 genders. These are:

Oroane (ᨕᨚᨑᨚᨕᨊᨙ) → Cisgender men

Makkunrai (ᨆᨀᨘᨑᨕᨗ) → Cisgender women

Calalai (ᨌᨒᨒᨕᨗ) → Transgender men (born with female bodies)

Calabai (ᨌᨒᨅᨕᨗ) → Transgender women (born with male bodies)

Bissu (ᨅᨗᨔᨘ) → Intersex people (people who “do not fit typical binary notions of male or female bodies”)

Oroane, makkunrai, calalai and calabai live their lives together without much discrimination for those outside of the “common two genders.” It does appear the calalai are a bit looked down upon as lazy but this is nothing compared to what transgender women can live in the West I guess.

Bissu people are the only ones with a completely different status. They are considered as unique spiritual figures embodying all genders. They are considered to be intermediaries between the human world and the divine, possessing the ability to communicate with the gods and spirits.

The Bissu play a crucial role in various cultural and religious ceremonies.

Interestingly enough, while their role was originally tied to animist religious ceremonies in particular and most Bugis are now Muslims, pre-Islamic rites are still performed to this day.

Still, some hardline Islamic groups, politicians, and the police have contributed to an increase in the discrimination of nonheterosexuals in recent years.

Quite unfortunate for a community that was so open-minded originally.

If you want to read more about these genders, I highly recommend this BBC article about them!

In any case, it’s now time to turn to what originally attracted me most.

The Lontara Script

The Lontara script is used for the Bugis, Makassarese, and Mandar languages. It is also called the Buginese script because most documents written in this script are for Buginese.

And yet, nowadays, this script has been replaced by the Latin alphabet in Bugis while the other two languages apparently still rely on it. A bit ironic if you ask me.

Like two of the other languages we’ll see this month, this script is an abugida, which means each character is actually a syllable that includes the vowel /a/ and diacritics are added around to change the inherent vowel to another one.

For example, ᨒᨚ /lo/ as in the word ᨒᨚᨈᨑ /lontara/, is the syllable ᨒ /la/ to which the vowel ᨚ is added.

The Lontara script only has 23 characters in total originally but a few new diacritics have been added in “Modern Bugis” to fit the needs of the language, such as a nasal sound or a glottal stop. They aren’t isn’t actually used in official documents though.

Interestingly enough, despite the Bugis language having many final consonants, there is no way to actually write them.

The word Lontara itself is therefore actually written as Lo (ᨒᨚ) ta (ᨈ) ra (ᨑ), even though it is pronounced properly as Lontara.

The Bugis word for the Lontara script is urupu sulapa eppa and it means “four-cornered letters,” representing the shape of these letters.

This script is an evolution of the Old Javanese script, or Kawi script, one of the rare scripts that even my computer, used to seeing strange scripts, refuses to display properly. 🤯

It is possible to type in the Lontara script with the Branah website. And it’s actually quite simple! Typing an ‘l’ writes the /la/ syllable. Press the /o/ key and the diacritic gets added to change the syllable to /lo/.

One thing, I can’t really get my head around, however, is the surprising fact there’s no agreed orthography for the Bugis language in the Latin alphabet, which means different people may write the same words in different manners.

Then again, I guess this shouldn’t be so surprising considering the fact that the word ᨈᨄ could very well represent either of the below words:

tapa — to roast

tappa — to form

tappa’ — gleam

tampa’ — sort of gift

tampang — string or tape

I wonder how the spoken and written versions of the language didn’t impact each other. As in, why the spoken language kept final consonants despite not being able to write them, or why ways to write them weren’t created to fit the need.

Then again, that’s what languages are.

Mysterious.

Bugis language basic facts

Bugis doesn’t follow a strict word order. Most common sentences are written in Verb-Object-Subject (VOS) but SVO can easily be found as well.

As a pro-drop language, the subject of sentences is often omitted. This is also because the subject is also expressed with a verbal marker.

Bugis has a definite article -e which is added after the word it represents. For example, oto-e (ᨕᨚᨈᨚᨕᨙ) means “the car.” When no definite article is used, it would be translated as having an indefinite article.

Bugis also requires the use of the definite article in situations where English wouldn’t. For example, “that house” wouldn’t need a definite article in English because of the presence of “that” but Bugis uses both a demonstrative word to mean “that” (yoro ᨐᨚᨑᨚ) and the -e particle too: yoro bola’-e (ᨐᨚᨑᨚ ᨅᨚᨒᨕᨙ).

While Bugis doesn’t have genders in general, proper names may add an ‘i’ (ᨕᨗ) in front for women and a ‘la’ (ᨒ) for men. For kinship, the words urane (man) and makunrai (woman) can also be added to give precision:

amure urane(ᨕᨆᨘᨑᨙ ᨕᨘᨑᨊᨙ) — uncleamure makunrai(ᨕᨆᨘᨑᨙ ᨆᨀᨘᨑᨕᨗ) — aunt

There’s no plural either in Buginese in general but, in case it is actually needed, reduplication can help serve that purpose. For example, ana’ (ᨕᨊ) means “son/daughter” while ana’ana’ (ᨕᨊᨕᨊ) means “children.”

The adjective mega (ᨆᨙᨁ) which means “many” can also be used to serve the same purpose:

mega otti (ᨆᨙᨁ ᨕᨚᨈᨗ) — bananas

Pronouns

Bugis has 8 different personal pronouns so the first thought you might have might be that it has a different word for He, She and It but that’s no the case. There’s actually only one form for all three but 2 different forms for the singular You and the plural You.

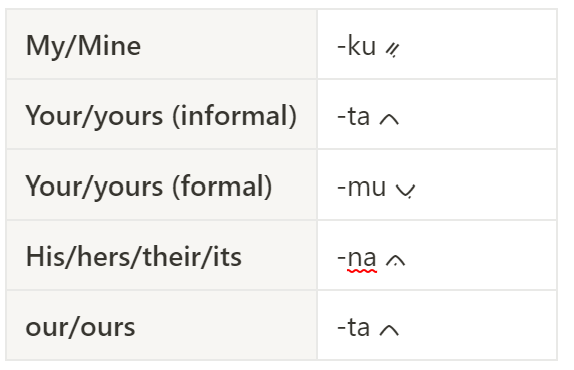

As for possessive pronouns, the difference between formal and informal for the second person is kept too:

For example, bo’bo’-ku (ᨅᨚᨅᨚᨀᨘ) is “My book.”

I find it quite interesting to see the same particle used for “our” and the formal version of “your.”

Another interesting point is the unique third-person pronouns. As you can see, despite the existence of 5 genders as discussed earlier, this separation doesn’t show up in pronouns. The third person can be used toward whoever no matter their sex.

Sentence construction

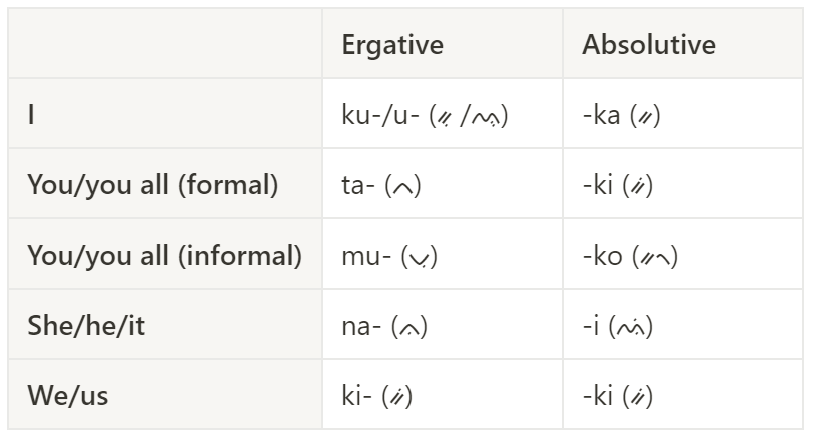

Bugis is what we call an ergative-absolutive language. Before you freak out like I did because the word ergative keeps escaping me, let me explain with a metaphor how such languages work.

Think of a game of soccer. In this game, the players who have the ball and are actively trying to score a goal are in the "ergative" case. They're the ones doing the action. But if a player is just standing there, or if they're the one being passed the ball, they're in the "absolutive" case. They're not actively doing the action, but they're still an important part of the game. So, in our soccer game language, we have different ways of talking about the players based on whether they're actively playing (ergative) or just receiving the ball (absolutive).

Basically, the ergative shows the subject and the absolutive shows the object.

The absolutive is also used for sentences using intransitive verbs, meaning verbs that don’t have an object.

Verbs and Tenses

As mentioned earlier, Bugis often drops the subject because it is also included in the verb itself. As it is an ergative-absolutive language, it uses two different ways to do so, with clitics:

Each verb is surrounded by the clitics needed to indicate the subject (and the object when needed).

For example, na-unu-w-i la Dafi oto-e. (ᨊᨕᨘᨊᨘᨕᨗ ᨒᨉᨃᨗ ᨕᨚᨈᨚᨕᨙ) can be divided as follows:

3 person singular Ergative (subject) - to kill - w1 - 3 person singular Absolutive (object) | Masculine-David | car-the.

Considering the typical word order VOS (and simple logic), the sentence ends up being “The car kills David.”

Verbs in the infinitive form use the prefix ma ᨆ. This prefix is sometimes kept in sentences, although I haven’t been able to find a clear answer on when it should be kept and when it should be taken off. (When the verb starts with a vowel, the /a/ in the /ma/ is often omitted.)

When it comes to tenses, Bugis uses keywords to place the sentence in time:

Present: The present only keeps the verb in its infinitive form and adds the absolutive pronoun clitic

more-w-i tomatoa (ᨆᨚᨑᨙᨕᨗ ᨈᨚᨆᨈᨚᨕ) → The old man coughs [Cough-3sgAbsolutive | Old man]

Future: Bugis uses the verb “to want” (ma-lo ᨆᨒᨚ) to before the main verb:

lo-ko manre (ᨒᨚᨀᨚ ᨆᨑᨙ) → You (informal) want to eat OR You’ll eat.

lo-i jokka (ᨒᨚᨕᨗ ᨍᨚᨀ) → He will go OR He wants to go.

Past: It can be inferred from the context or use different suffixes. The most common I found was /n’/

Mate-n-i (ᨆᨈᨙᨊᨗ) → He died.

Ma-anru-n-i (ᨆᨕᨑᨘᨊᨗ) → He fell down.

As for the negation, the prefix /de’/ followed by the ergative makes the trick:

De’-u yoka ku bola-ku. (ᨉᨙᨕᨘ ᨐᨚ ᨀᨘ ᨅᨚᨒᨀᨘ) → I don’t go to my house. [Negation-1sg Ergative | go | preposition | house-my]

Example sentences

Oe! Aga kareba? (ᨕᨚᨕᨙ!ᨕᨁ ᨀᨑᨙᨅ?) → Hi! How are you?

Tarima Kasi (ᨈᨑᨗᨆ ᨀᨔᨗ) → Thank you. (From the Indonesian Terima Kasih)

Iye’ / De’ (ᨕᨗᨐᨙ / ᨉᨙ) → Yes / No

Tegaki monro? (ᨈᨙᨁᨀᨗ ᨆᨚᨑᨚ?) → Where do you live?

Malufu’-ka. (ᨆᨒᨘᨃᨘ ᨀ) → I’m hungry.

U foji Aleta’ (ᨕᨘ ᨃᨚᨍᨗ ᨕᨒᨙᨈ) → I like you.

Mabella bola-na (ᨆᨅᨙᨒ ᨅᨚᨒ ᨊ) → His/Her house is far.

Asu ga ye? (ᨕᨔᨘ ᨁ ᨐᨙ?) → Is this a dog? [Dog | Yes-No Question | This]

Where to learn

Finding resources to learn Bugis is not easy.

There are a few papers I was able to refer to but the best was this clear 60-page paper from 2014.

Apart from this, there’s one video from the very interesting YouTube channel gathering recordings of simple sentences in hundreds of languages ILoveLanguages!

Considering the language is spoken in Indonesia, I wouldn’t be surprised if there were more resources in Indonesian though.

Similarly, since the country was occupied by the Dutch for a long time and the language was impacted by this, I guess there should also be more resources in Dutch as well.

The website Sealang, a great resource for quite a few languages in SouthEast Asia also has a small dictionary that can be helpful.

Final words

Discovering Bugis, or Buginese if you prefer, was—as usual—a beautiful journey. Not only was its script an absolute beauty with its simple squared shapes and dots in and around, but it was also a lot of fun to learn the basics of a VOS language as I’m not used to this word order.

As if this wasn’t enough, reading about the Bugis culture and its 5 genders was yet another great reminder we should all learn from other cultures.

I hope you enjoyed this discovery just as much as I did!

And if you know even more about the Bugis people, language, or culture, please do share!

W doesn’t have a meaning per se. It is an epenthetic sound often added after the verb if the last letter is a vowel.

So, my dad is Bugis and can speak the language but I grew up in Malaysia, speaking English and Malay. I knew some rudimentary phrases and words (mostly forgotten) but my dad avoided actively teaching me despite having asked him a number of times. Now in my 30s, I have a desire to learn it or at least become reacquainted with it.

One thing I noticed from the Latin transliteration is that its very difficult to convey how the words actually sound with the letters alone. For example, the pronunciation for mega (ᨆᨙᨁ) sounds more like "ma-e-ga". I can't imagine how hard it would be to learn Bugis without any native speakers for guidance, especially given the ambiguous spellings and how different it sounds from western languages.

You said, "... the same particle [is] used for 'our' and the formal version of 'your.' " But in the chart above that, "ta" is listed as both "our" and the informal version of "your". I'm pretty sure it's the table that is incorrect.