Lesser-Known Languages (LKL) — Aymara

A language all about its suffixes, with 3 ways to mean "we"

While everybody knows there are countless languages spoken around the world, I’ve always seen South America as a rather “simple” area where only Spanish and Brazilian Portuguese were spoken.

Sure, I did think there was a time when the “Mayan” language was spoken but that was it. I even thought Aztec, Quechuan, and Mayan were different terms for the same language.

Oh, how wrong I was.

In 2019, at the Polyglot Conference in Japan, I discovered the existence of Nahuatl, an Aztec language1 spoken by 1.5 million people today. While I never dug deep into it, it showed me South America was more diverse than I thought.

Since then, I’ve discovered a few important facts I wish everybody knew:

Latin America is home to hundreds of languages

The “Mayan language” isn’t a thing. There’s a family of languages known as the Mayan languages family, some spoken by hundreds of thousands of people and some by only a few dozen. The same goes for Quechuan.

While Spanish and Brazilian Portuguese are official languages in most of Latin America, they are not the first language of many of these countries’ citizens.

And today, we’re diving into one of the largest ones, spoken by over 2 million people across Bolivia, Peru, and Chile: Aymara, also known as Aymar Aru in its language.

But first, let’s discover the Aymara people’s history. A difficult story, akin to many others in the area.

Aymara people vs colonization

The Aymara people have a long and complex history that dates back thousands of years. They are indigenous to the Andes mountain region of South America, which includes parts of Bolivia, Peru, Chile, and Argentina.

Some archaeological evidence suggests that the Aymara people may have inhabited the region for at least 800 years but some estimate they could have been there for more than 5,000 years.

In the 15th century, the Inca Empire expanded into the region, and the Aymara people were incorporated into the empire. The Aymara people resisted Inca rule and engaged in frequent rebellions against the empire. This meant that they were already used to resisting invaders when the Spanish arrived in the 16th century.

The Spanish conquest of the region was brutal and led to the deaths of millions of indigenous people, including the Aymara. The Aymara people fought fiercely against Spanish colonization, but they were ultimately conquered and subjected to centuries of oppression, forced labor, and land seizure. During this time, they were forced to adopt Catholicism and Spanish culture, and their own language and cultural practices were suppressed.

In the 20th century, the Aymara people began a movement for autonomy and self-determination. They formed political parties and trade unions, and in the 1950s and 1960s, they participated in several uprisings against the Bolivian government.

The Aymara people also fought for the recognition of their language and culture, and today, the Aymara language is recognized as an official language in Bolivia and Peru, as well as a minority language in Chile.

Origins and Classification

While I tend to avoid erring on etymology and language family classifications, Aymara’s gone through so many theories I figured it needed its own section.

The Aymara language is sometimes considered related to Quechua.2 While the two have some similarities, most linguists today consider these as features that arose from a prolonged cohabitation in the same area.

It was once called “the language of the Colla,” which would have apparently been the name for an Aymara nation but, again, this was actually a mistake as the language these people seem to have been Puquina.

Cerrón-Palomino provides the most comprehensive explanation of the history of the Aymara people. According to him, the name Aymara originated from the Quechuaized place name "ayma-ra-y," which means "place of communal property."

Finally, it’s worth mentioning that Aymara doesn’t come from the Aymara words jaya (ancient) and mara (year, time). This seems to have been what linguists call a folk etymology3.

The Aymara language

Today, there are about two million speakers in Bolivia, 500,000 in Peru and a few thousand in Chile. While this is larger than most other indigenous languages, it is also a lot lower than it used to be. Indeed, Aymara was the dominant language over a larger area than today.

Many Aymara-speaking communities now speak Quechua or Spanish instead.

And yet, the language is still thriving. The advancement of the internet has also allowed many native speakers to create their own content in the language and teach it.

Alrighty then, let’s get nerdy. 🤓

Overview

Aymara only has three used vowels: a, i, and u. Each also has another form pronounced longer: ä, ï, and ü.

Of course, as its speakers have been exposed to Spanish for generations and now also use loanwords, the vowels e and o can be found in Aymara texts too.

Aymara follows a Subject-Object-Verb (SOV) sentence structure but the use of suffixes also allows meaning to be retained even if the order is changed.

It seems Aymara has what is called a three-value logic system. In such a system, statements can be assigned one of three truth values: "true" if the statement is definitely true, "false" if the statement is definitely false, or "unknown" if there is not enough information to determine the truth value of the statement.

For example, consider the statement "John is taller than Mary." In a three-value logic system, the statement could be assigned an "unknown" value if there is not enough information about the heights of John and Mary to determine whether the statement is true or false. This impacts how sentences are constructed in Aymara but I haven’t been able to find exactly how.

If you do know, let me know in the comments!

Finally, one important aspect of Aymara is its habit of vowel deletion, also often called ellision. While this only happens when spoken out loud in many languages, Aymara actually reflects this practice in written form.

One of the most simple reasons to delete a vowel is when the same vowel appears in a row, even if its the last vowel of one word and the first of the next.

Markat alta. → I bought from the town.

In this example, Marka is “town” to which the suffix ~ta (indicating a movement from a place of provenance) was added. However, since the verb alta (from altaña starts with an a).

Basic suffixes

Aymara is what we call an agglutinative language, a type of language in which words are formed by stringing together smaller, meaningful units called morphemes. These morphemes can include things like prefixes, suffixes, and other word elements that can be added to a base word to change its meaning or indicate tense, case, or other grammatical features.

In Aymara’s case, suffixes are where everything happens.

For example, the word khiti means “who.” Depending on the suffix used, the meaning evolves as follows:

khitita → whose

khitimpi → with who

khitiru → whom

khititaki → from whom

khitinki → to whom

etc.

Suffixes are used to change almost every word in sentences, from noun to indicate their position and details about them, to verbs to express the tense, aspect, and other details.

Here are just a few common ones:

~naka → Indicates the plural

qala = stone but qalanaka = stones

~sa → Principal emphatic suffix for questions

~wa → principal suffix giving an affirmative feeling to the sentence. Can be translated as the verb “to be” in some cases.

~xa → emphatic suffix that often requires a “principal suffix” somewhere else in the sentence,

Kunas akaxa ?→ What is this? [What-s

athis-xa]Akax thakiwa. → This is a path. [This-x

apath-wa]

Interestingly enough, the plural suffix is only required once in any sentence and can be added to other terms instead:

Akanakax qalawa = Akax qalanakawa → These are stones.

In the first case, it was added to “this” (aka). The copula is implied.

Pronouns

As done in Spanish, personal pronouns are often omitted and are only used to put an emphasis on the person. There are only four:

naya → I

juma → You (singular)

jupa → He, she

jiwasa → We

To make the plural form of these pronouns, the plural suffix ~naka is simply added to create:

nayanaka → We

jumanaka → You (plural)

jupanaka → They

jiwasanaka → We

But wait! What’s up with the three ways to say “we,” you ask?

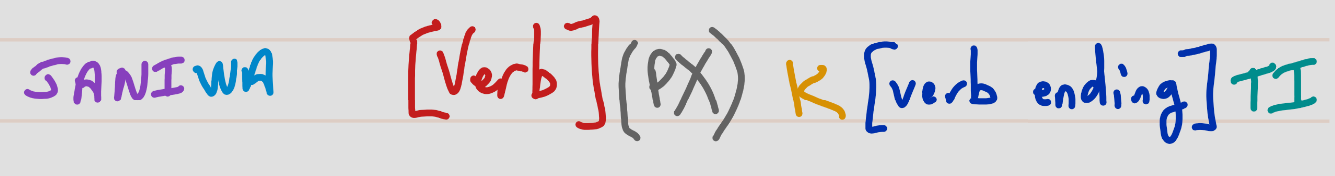

Well, here’s an awful drawing I made based on this video explaining them in Spanish:

In short:

Jiwasa is used when a third person is present in the conversation and you’re excluding them (without actively talking to them)

Nayanaka is used when a third person is present in the conversation and you’re excluding them while talking to them

Jiwanaka includes everybody.

If you speak Aymara and know more about the nuances, please let me know in the comments!

Contrary to most words of the language, pronouns don’t require any suffixes unless you want to emphasize the subject.

Aymara has four demonstrative pronouns indicating how far the topic is from the speaker:

aka → this (closer to speaker)

uka → that (farther from speaker, such as on the other side of a room)

khaya → that over there (quite far from speaker, such as across the street)

khuri → that, way over there (very far from speaker, such as across a field)

When it comes to expressing possession, Aymara relies on a few suffixes:

~xa → my, as in utaxa (my house)

~ma → your, as in sutima (your name)

~pa → his/her/their, as in awkipa (his/her/their father)

~sa → our, as in taykasa (our mother)

These suffixes can then be followed by more suffixes when needed in sentences, such as in the common sentence:

Kunas sutimaxa? → What is your name?

Here, kunas means “what” and is followed by the word suti with two suffixes

~ma → your

~xa → question marker replacing the verb “to be”

They can also be preceded by the suffix ~naka for plural words:

Kullakanakama→ Your sisters (with kullaka meaning “sister”).

As a final note on possession, the suffix ~na is used in other cases:

wawanakan(

a) iskuyla → The children’s school [Child-naka-naschool]

The Present Tense

Conjugation Aymara is quite complicated as it relies on combining a bunch of suffixes to the verb stem. In some cases (like the future and past simple tenses), the last vowel of the verb stem may need to be modified to a long vowel (see one example in the next section below) but we won’t cover this today as we’ll focus on the present tense, negation, and interrogations.

Verbs in Aymara all end in ña.

To conjugate them, it is necessary to keep only the stem but what is considered stem changes depending on whether the verb will be conjugated in the singular or plural:

When in the singular, the vowel preceding ña is not considered part of the stem and gets erased:

For ikiña (to sleep), only ik is kept to conjugate

For qilqaña (to write), only qilq is kept to conjugate

When in the plural, everything but the ña is considered stem:

For ikiña (to sleep), iki is kept to conjugate

For qilqaña (to write), qilqa is kept to conjugate

When conjugating in the plural, an extra suffix4 ~px~ is added right before the verb ending.

Furthermore, another suffix we’ve already seen before needs to be stuck to the end of the verb to make it affirmative: ~wa.

Put into a table, here’s the present tense of the verb qilqaña:

Want to ask a question in the present tense? Follow the same table and change the affirmative suffix ~wa to the interrogative one ~ti. For example:

Qilqapxiti? → Do they write?

Sarapxtanti? → Do we (all) go?

What if you want to use the present continuous, you ask? Well, in this case, the stem is everything but ña, whether singular or plural. Add to it yet another suffix right after the stem and before any other one:

~sk (singular):

Qilqisktwa. → I am writing.

~ska (plural):

Saraskapxiti? → Are they going?

What about the negative in the present tense?

Well, Aymara makes things just a tad more confusing to learners. Indeed, it requires:

The Aymara word for “no”: jani

With the principal suffix ~wa

The verb stem (with three letters taken off in the singular and two in the plural) followed by

The plural suffix ~px if needed

The negative suffix ~k

The final suffix ~ti that we just saw being used for interrogations

To get the final result:

Janiwa qilqktati. → You don’t write.

Janiwa ikipxkiti → They don’t sleep.

That last suffix brings a new question to the table. How’s a negative present tense question done? Well, it’s actually somehow simpler.

The ~ti suffix replaces ~wa after jani and the verb ends with its tense ending. One slight change there is that the first person present tense ending then becomes ~ta instead of ~t. Got it? Here’s an example:

Janiti sarapxkta? → Don’t we go? (exclusive)

Janiti churapxktan? → Don’t we (all) give? (inclusive)

Phew! 🥵

And that’s only the present tense!

Simple sentences

To close things off, let’s turn to a few more random example sentences.

Kamisaki? - Waliki! → Hello, how are you? - Good!

Aski urukïpana → Good morning. (just add ~ya when answering to this)

Jikisiñkama → Until next time / See you soon (just add ~ya when answering to this)

Jisa / Janiwa → Yes / No

Yuspara. → Thank you.

Pirtunitayya → Sorry

Kawkinkiritasa? → Where are you from?

Akax punkunakawa. → These are doors.

Akax jayuti? Jïsa. Akax jayu wa. → Is this salt? Yes, it is salt.

Utaxax jach’awa. → My house is large.

Qharurukama. → Until tomorrow. / See you tomorrow.

Awtunakapax ch’iyarawa. → His cars are black.

Kawkirus saräta? → Where are you going to go?

kawkirus → kawki (where) + ~ru (direction suffix) + ~s

a(principal marker)saräta → sara

ña(to go) + ¨ (1st person future) + ~ta (future interrogative suffix)

Where to learn Aymara?

While I found quite a lot of basic information about Aymara in English, these all lacked example sentences (such as the Wikipedia page).

I did find one extremely detailed free PDF from the Peace Corps but it is quite old and relied on an older way to write (such as writing naka as naca) which made me doubt the accuracy of the rest of the content.

On the contrary, there’s a lot of detailed information out there about Aymara in Spanish, which makes sense as most Aymara speakers also speak Spanish and are situated in Latin America.

YouTube is filled with videos explaining conjugation patterns and some grammar patterns. My favorite ones were:

Aymara con Roman Pairumani → This one has countless 1-hour online classes he’s taught, all available for free. Roman also has two books about Aymara available online.

There are also tons of freely available PDF textbooks online:

Guía Pedagógica para el aprendizaje de la lengua Aymara (mostly about vocabulary)

Guías Pedagógicas del sector lengua indígena: Aymara (for teachers so it doesn’t explain much but it has many texts in both Aymara and Spanish for reading practice)

Aymar Aru (textbook for children learning Aymara).

If you speak Spanish, however, I’d highly recommend checking out this webpage filled with downloads about everything Aymara-related, including dictionaries, glossaries, textbooks, and bilingual texts.

Finally, there’s a rather interesting Facebook page filled with information about the language and even some current videos, such as an Aymaran version of a song from the recent Mario movie: AYMAR YATIQAÑA-Aprender Aymara con Elias Ajata.

Final thoughts

I remember feeling completely lost when I researched the Mayan language K’iche last year. Using so many prefixes and suffixes messed with my mind which wasn’t used to it.

This time, however, Aymara felt less like a beast and more like an intricate puzzle. I reckon it’s because I’ve researched enough languages using suffixes in the past year to not be scared anymore.

I absolutely loved discovering Aymara5.

It's a beautiful language that, while impressive with its long words, probably isn’t so hard in the end once you get the hang of which suffix is used for what. By the end of writing this essay, suffixes like ~naka, ~wa, or ~px had no secret for me.6

Being one of the few Native American languages with over 1 million speakers and being recognized as an official language in two countries, it could very well strive in the future, especially as more and more native speakers start teaching it online.

Creating current content like this will certainly help it grow further and faster.

I would also highly recommend listening to some Aymaran music. Every word of this piece was written listening to what I found on this YouTube channel (even though some songs were in Spanish unfortunately) which was a fresh change of air for me.

If this piece made you even more curious about other languages in Latin America, get ready because we’ll cover three more in the incoming weeks and I’m willing to bet you won’t know them all!

Also called Nahuan languages

Another language I once thought was simply another name for Aztec and Mayan. Again, whoops.

I had never heard this term but I kinda like it!

Well, to be accurate, an infix

And realizing I can still understand Spanish with ease!

Well, they probably still do but I haven’t found them so we’ll just say they don’t.

A THREE VALUE logic system?! Semanticists, look out!!